Maurice Cole was born March 13, 1954, in the Terang Hospital in the middle of western Victoria, not super far from the surf zones he’d later occupy. Except he wasn’t.

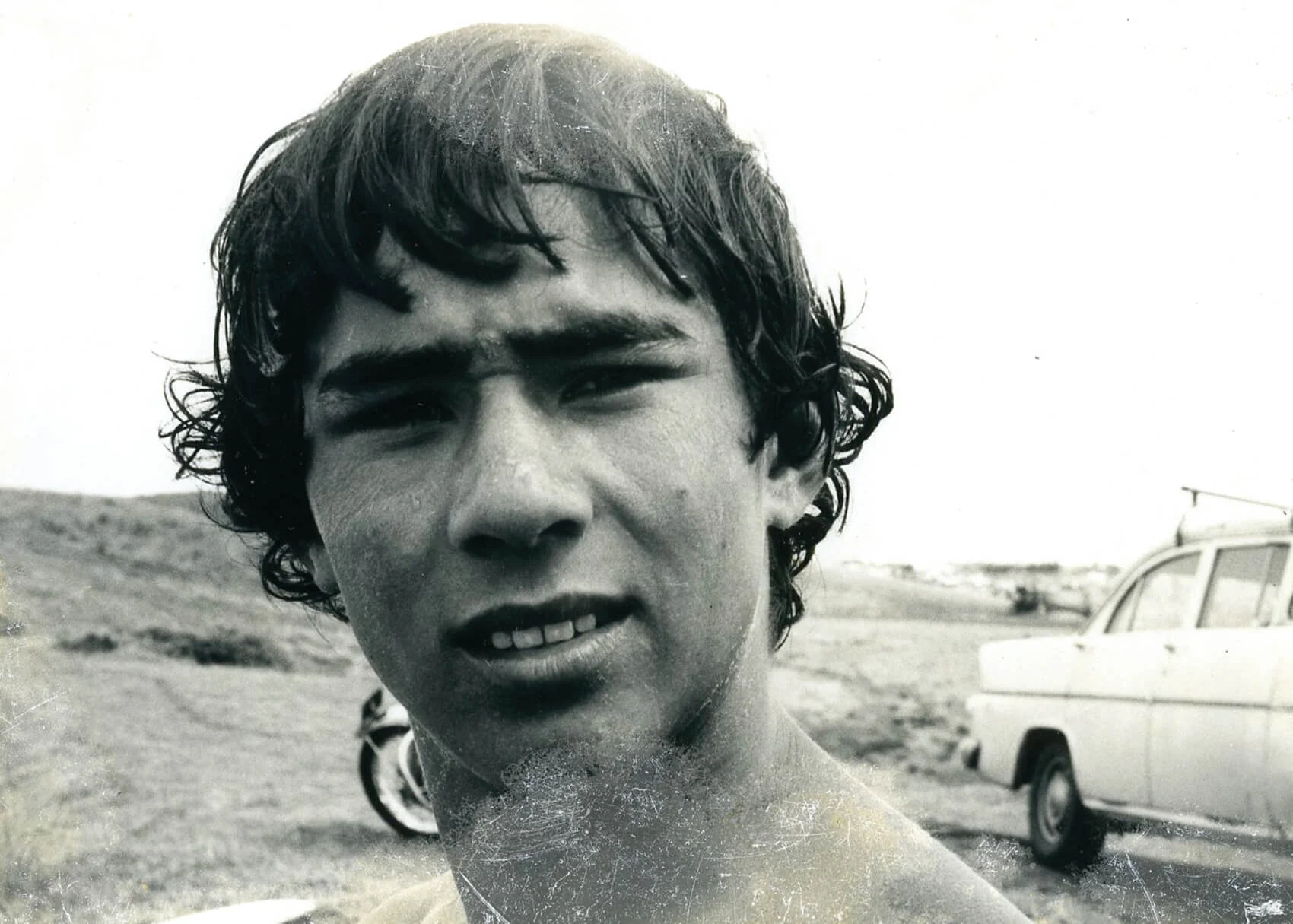

The kid born that day only became Maurice Cole after being adopted immediately following his birth by Frank and Mary Cole, a sturdy Anglican couple from Ballarat, some 80 miles north-east of Terang. Maurice’s parents later adopted another child, Maree, and they never hid the fact of adoption from their two kids. But Maurice wore the label in unsettled fashion. Maybe it’s a part of why he struggled to contain the explosive energies that arose within him as he grew; certainly it’s a part of the story he tells himself about his life. He recalls as a child being driven past a big dark building, the Ballarat orphanage, and being told that if he didn’t behave, he’d be going back there. That’s what I am, he thought, an orphan. Something was unmoored, driven yet adrift.

Meanwhile, he considered himself a timid little “Sunday School boy” who was made to attend church two or three times a week with his parents, Mary being a pioneering female member of the Ballarat Anglican Synod. Maurice never saw the ocean until the family moved down to the coast at Warrnambool in 1960. “We were made to go to church in those days,” he says, “you didn’t have a choice. Which became a real problem when I started surfing.”

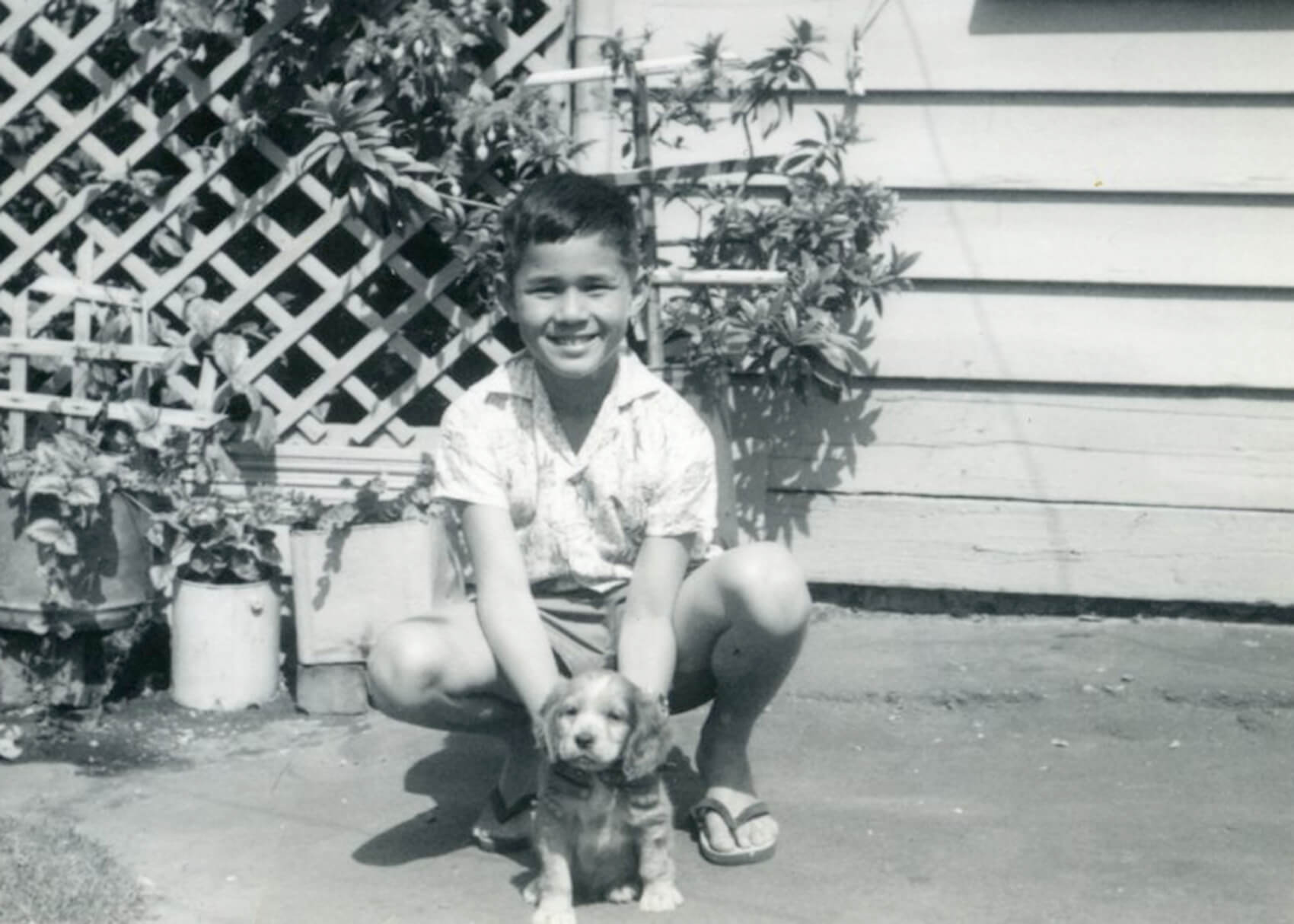

Warrnambool was far from a major city, yet it wasn’t a hick town on the outskirts. It had its share of wealthy citizens who’d profited from Australia’s long series of farming booms; in the early 1960s it was still thriving on the post-war wool trade. Frank Cole seized the day, developing the biggest plant nursery in the area, and later owning a gift shop. The first day of real school, Maurice walked in the front gate, through the school grounds, and straight out the back door. The second day, he climbed up a fir tree and hid in it. He made a few friends and tried not to draw attention to himself, steering clear of sports, but couldn’t always avoid the bullies you’d find in any country town schoolyard of the 1960s. He didn’t fight back, he says, “because I didn’t know how”.

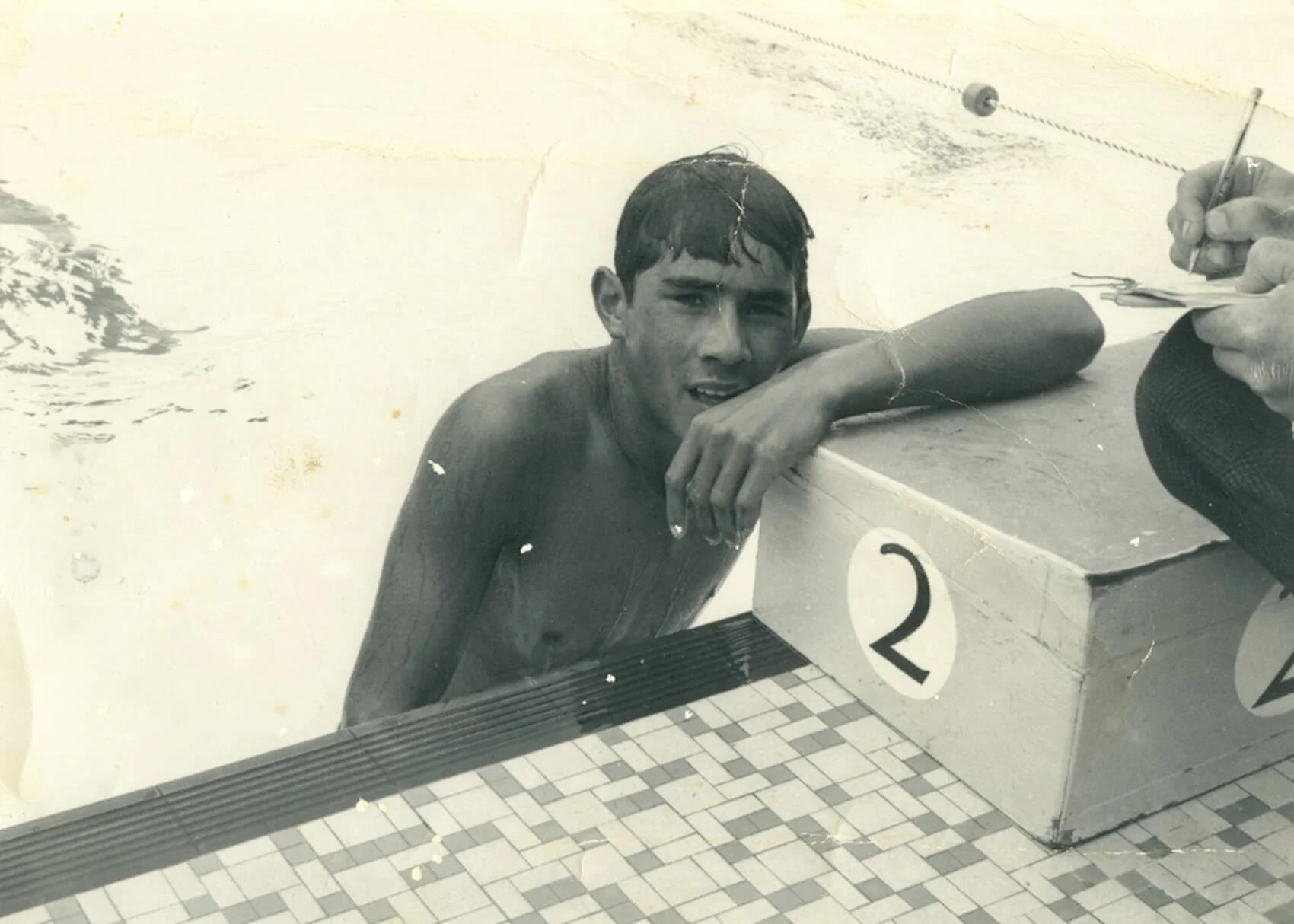

Surfing fell on him out of the blue one day in the summer of 1966, when he found himself at the beach with five shillings - the old British-inspired currency – in his pocket. By February that year he could have changed it to 60 cents, a bloody fortune. Instead he spent it on renting a surfboard. A big white-pigmented thing over nine feet long. Maurice walked the board out across a gently sloping sandbar through waist-high whitewater, strained his skinny 12-yearold body to turn it around, caught one of the little waves, and stood up. “All of a sudden my goal became to buy myself a surfboard. I was doing paper rounds and odd jobs like that. So I saved up $36 and bought one second hand off a guy called George Saffron from Ocean Grove. A 9’3” with a green GT stripe and a big D-fin. We didn’t have any racks on the car or anything, but I had a bike and I dunno how I did it but I rode with the board down to the beach. My passion was really tested by the logistics.” Maurice dragged that thing to the surf and back until one side of the tail wore off, then he flipped it over and wore off the other side. He reckons this was the first pintail he shaped. He repaired it with a builder’s glue named Plasti-Bond, and joined the local volunteer lifesavers’ club so he could store the board nearer the surf. The lifesaver disciplines, exercise drills and the rest, irritated that rebellious streak; when he tricked his way out of doing them, the club captain suspended him.

“But I’d been watching,” he says, nearly 50 years later. “This little building down in the dunes, in this nook and cranny. The Warrnambool Boardriders Club. And all these cars. A big Valiant with a full V8 and twin pipes and mags. A customised Holden FJ. Mini Coopers, MG sports. And when I first saw those guys surfing, well they could surf. I told the lifesavers’ captain to get fucked.

Within 24 hours I was in Warrnambool Boardriders.”